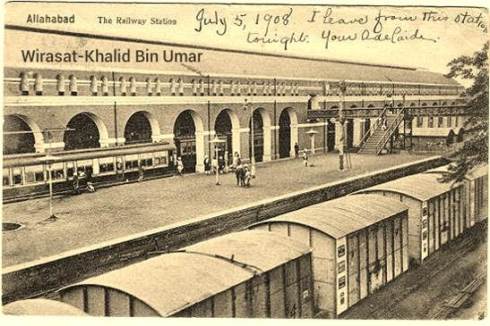

Terra Diaguita Boutique Hotel

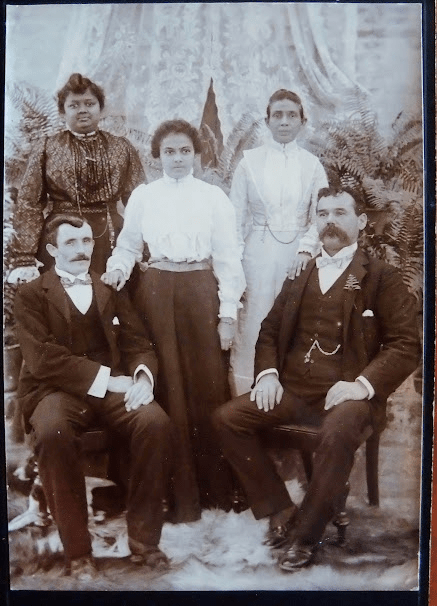

I never gave much thought to the name of the Hostel…Terra Diaguita Boutique Hostel in La Serena, Chile when I found and booked us rooms online for our South American trip in March/April 2017. Upon arrival, it looked like any other “hole in the wall hotel”…that was until we walked into the small lobby…..then the magical nature of this place hit us both. There were plants and seating areas everywhere…. art and artifacts on every wall and surface. The walkway leading to the rooms passed through the back garden. The rooms actually looked like cottages with the outside walls painted a warm yellow.

One of the many areas with plants and artifacts

Seating area

Pathway to the rooms through the Garden

Individual Rooms

Individual Rooms

The next morning, after I had time to settle in and explore the local area, I decided to take a closer look at the artifacts in the hostel. What was the meaning of the name..DIAGUITA…and did it have a relationship to the artifacts and art.

Through further research, I have since learned that these Pre-Columbian Diaguitas had great cultural traditions and in the 21st Century, they have a connection to a large Canadian Company…(Barrick Gold, the largest gold mining company in the world with headquarters in Toronto, Canada). For some, this is a contentious relationship…and today, these Indigenous People are still struggling to retain their ancient culture, art and traditions. If this sounds familiar to stories you have heard about Canada’s Indigenous Peoples….it is.

Book Cover in a Book Stall in the market

Digging further into the history of the Indigenous peoples of Chile….I saw the exact same story playing out over the centuries as the Spanish Colonizers came in contact with the Indigenous Peoples…the same story we have here in Canada with just a change in names… here it was the British and French Colonizers.

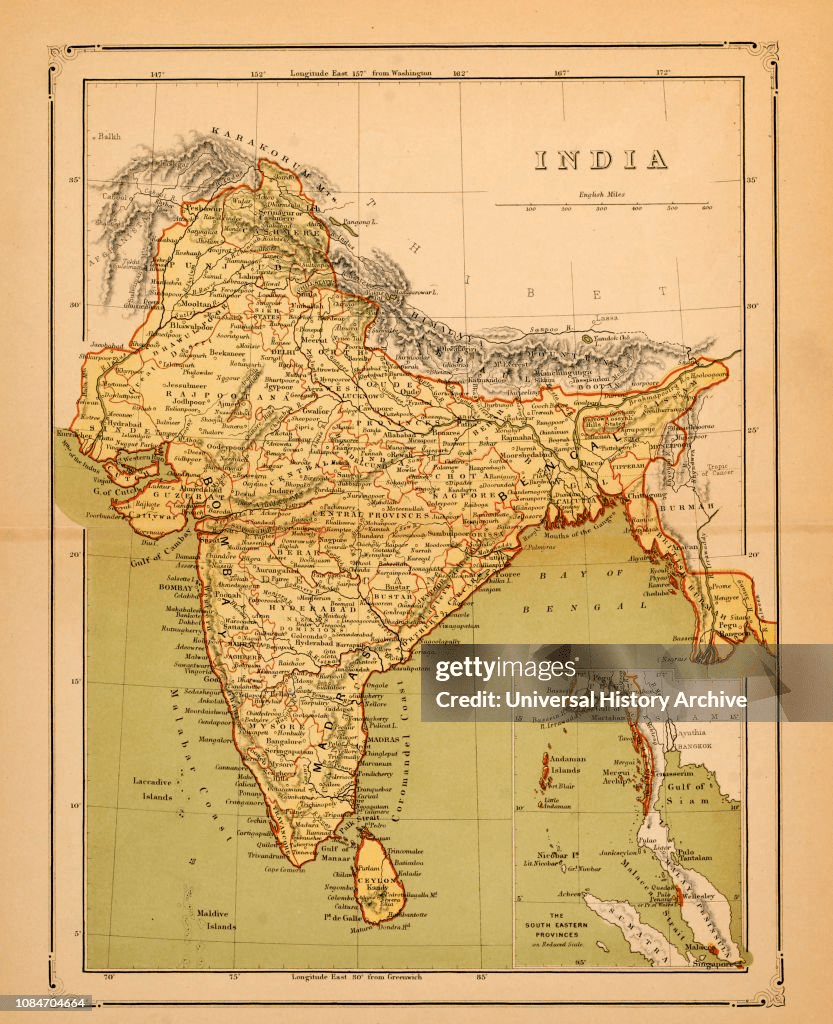

Chile is situated in southern South America, bordering the South Pacific Ocean and a small part of the South Atlantic Ocean. Chile’s territorial shape is among the world’s most unusual. From north to south, Chile extends 4270 km (2,653 mi), and yet it only averages 177 km (110 mi) east to west.

The Chilean government currently recognizes nine indigenous groups within its borders, the Atacameño, Aymara, Colla, Diaguita, Kawashkar, Mapuche, Quechua, Rapa Nui, and Yagán peoples, each of which has a rich history and culture.

I was familiar with pre Columbian civilizations such as the Incas, Aztecs and Mayans….but the Diaguita I hadn’t known. I had never really considered that there were likely many other groups that had been living in South America for thousands of years.

The Indigenous Law Distribution of people from Kawesgar in the south to Aymaras in the North

From Indigenous News.org (Website)

“The largest indigenous group in Chile is the Mapuche people (approximately 85% of all indigenous people in Chile), which is concentrated in the south. The Diaguita are a much smaller group living in the more northernly regions of the country. Although difficult to summarize, the situation of most indigenous people is one of poverty and marginalization as a result of the discrimination from which they have historically suffered.

After the first Spanish colonizers settled in the central valley in Chile, the native population began to disappear as a result of the conquest and colonization, and the survivors were gradually absorbed and integrated into the nascent Chilean population. Several attempts by the Spanish to subjugate the Mapuche failed and the Crown recognized the independence of these peoples in various agreements (parlamentos), respecting their territorial sovereignty south of the Bíobío river, which became a real, though porous, border between two societies and two cultures. The Chilean Republic maintained the same relationship with the Mapuche nation during the first half of the nineteenth century, but Chilean forays into the region gradually weakened indigenous sovereignty and led to several conflicts.

Finally, in 1888, Chile embarked upon the military conquest of Araucanía in what became known in the official history books as the “pacification of Araucanía”, which brought about the integration of the region into the rest of the country. In addition, as a result of the war of the Pacific (1879-1883), the Aymara, Atacameño, Quechua and Colla groups in the north of Chile were also integrated. The main outcome of this period for native peoples was the gradual loss of their territories and resources, as well as their sovereignty, and an accelerated process of assimilation imposed by the country’s policies and institutions, which refused to recognize the separate identities of indigenous cultures and languages. Chilean society as a whole, and the political classes in particular, ignored, if not denied, the existence of native peoples within the Chilean nation. The exclusion of native peoples from the popular imagination in Chile became more pronounced with the construction of a highly centralized State and lasted, with a few exceptions, until the late 1980s.

President Salvador Allende, who was elected in 1970, introduced various social reforms and speeded up the process of land reform, including the return of land to indigenous communities. The military regime that came to power following the coup led by Augusto Pinochet reversed the reforms and privatized indigenous land, cracking down on social movements, including those representing indigenous people and the Mapuche in particular.

The treatment of indigenous people as if they were “invisible” did not begin to change until the decline of the military regime, when their most representative organizations began to push a number of demands for recognition of the rights denied to them. The return to democracy in 1989 signaled a new phase in the history of the relationship between indigenous peoples and the Chilean State, embodied in the Nueva Imperial Agreement signed by the then presidential candidate, Mr. Patricio Aylwin, and representatives of various indigenous organizations, and culminating in the 1993 Indigenous Peoples Act (No. 19,253), in which, for the first time, the Chilean Government recognized rights that were specific to indigenous peoples and expressed its intention to establish a new relationship with them.

Among the most important rights recognized in the Act are the right to participation, the right to land, cultural rights and the right to development within the framework of the State’s responsibility for establishing specific mechanisms to overcome the marginalization of indigenous people. One of the mechanisms set up in this way was the National Indigenous Development Corporation (CONADI), which acts as a collegiate decision-making body in the area of indigenous policy and which includes indigenous representatives.

To back up the State’s indigenous policy in this new phase, the Government of President Ricardo Lagos set up the Historical Truth and New Deal Commission, chaired by former President Patricio Aylwin and consisting of various representatives of Chilean society and indigenous people. Its mandate was to investigate “the historical events in our country and to make recommendations for a new State policy”. The Commission submitted its report, conclusions and proposals for reconciliation and a new deal between indigenous people and Chilean society in October 2003.

In September of 2008, after nearly two decades of struggles, the Chilean government ratified Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO 169), which guaranteed additional rights to the indigenous peoples living in Chile. In particular, ILO 169 supports the rights to consultation, property, and self-determination. The law officially went into effect in September of 2009, and has only now begun being litigated in the courts. Despite the victory ILO 169 represents for indigenous rights, in reality, many conflicts and fights remain to be had between the Chilean government and the indigenous peoples living within its borders.”

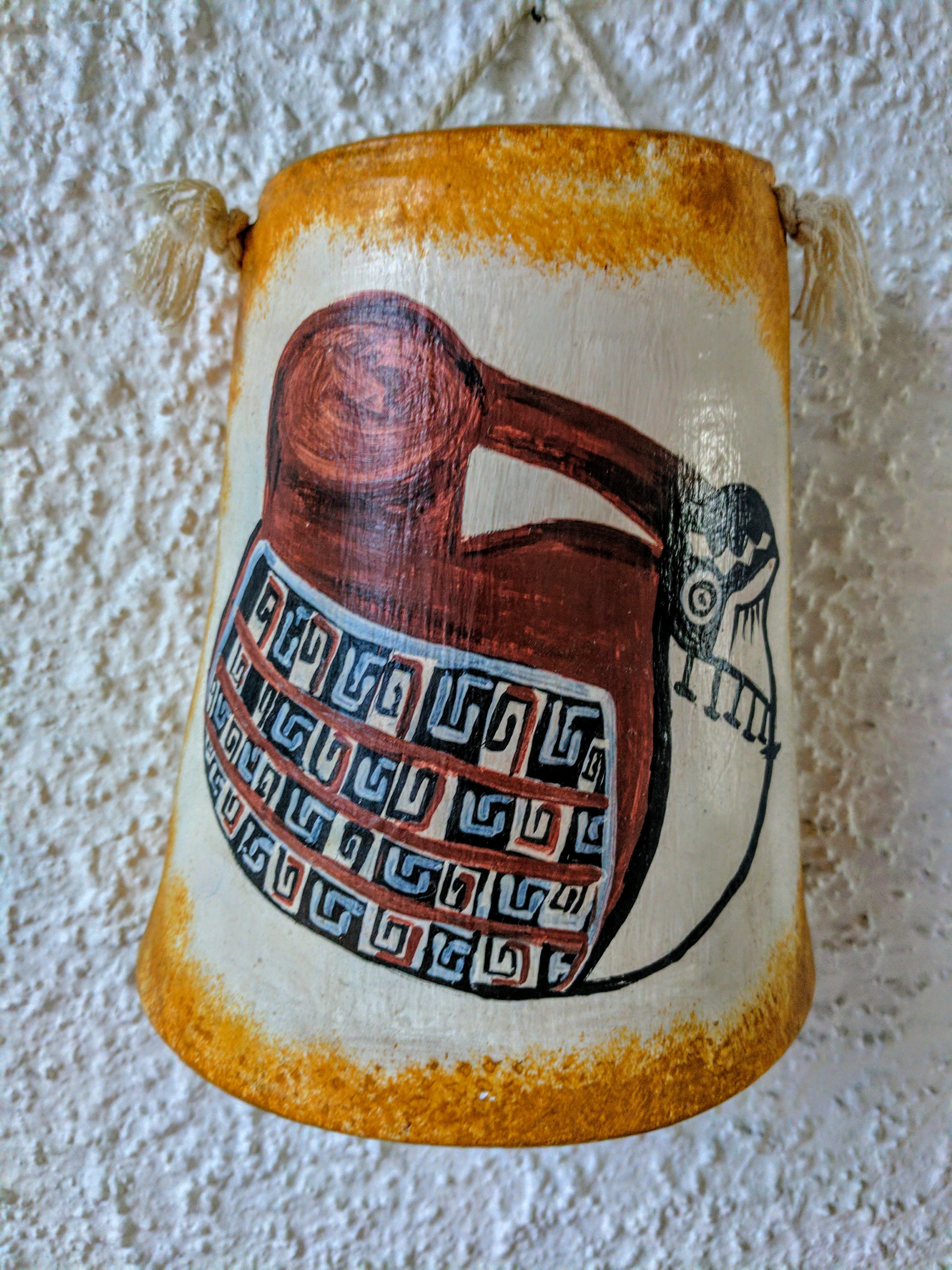

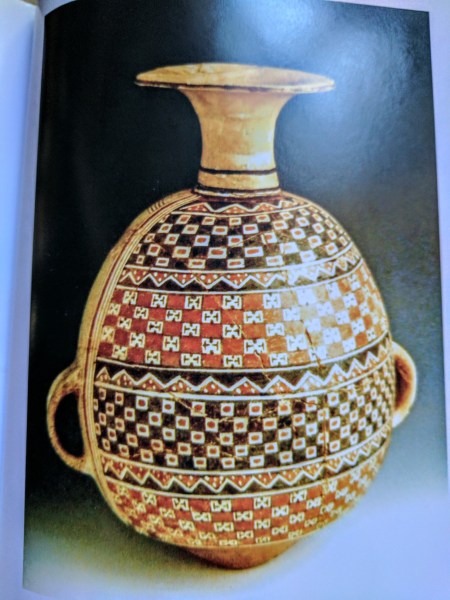

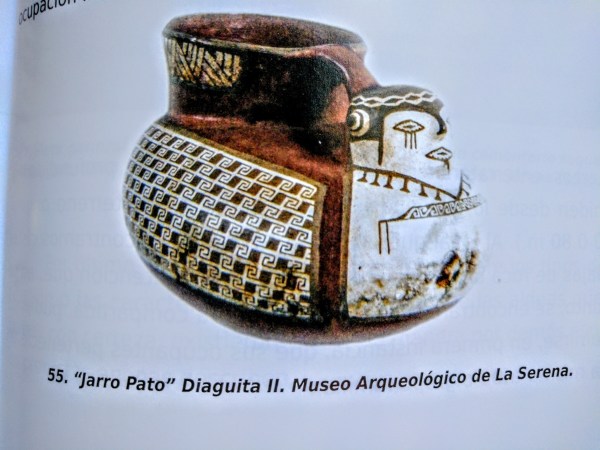

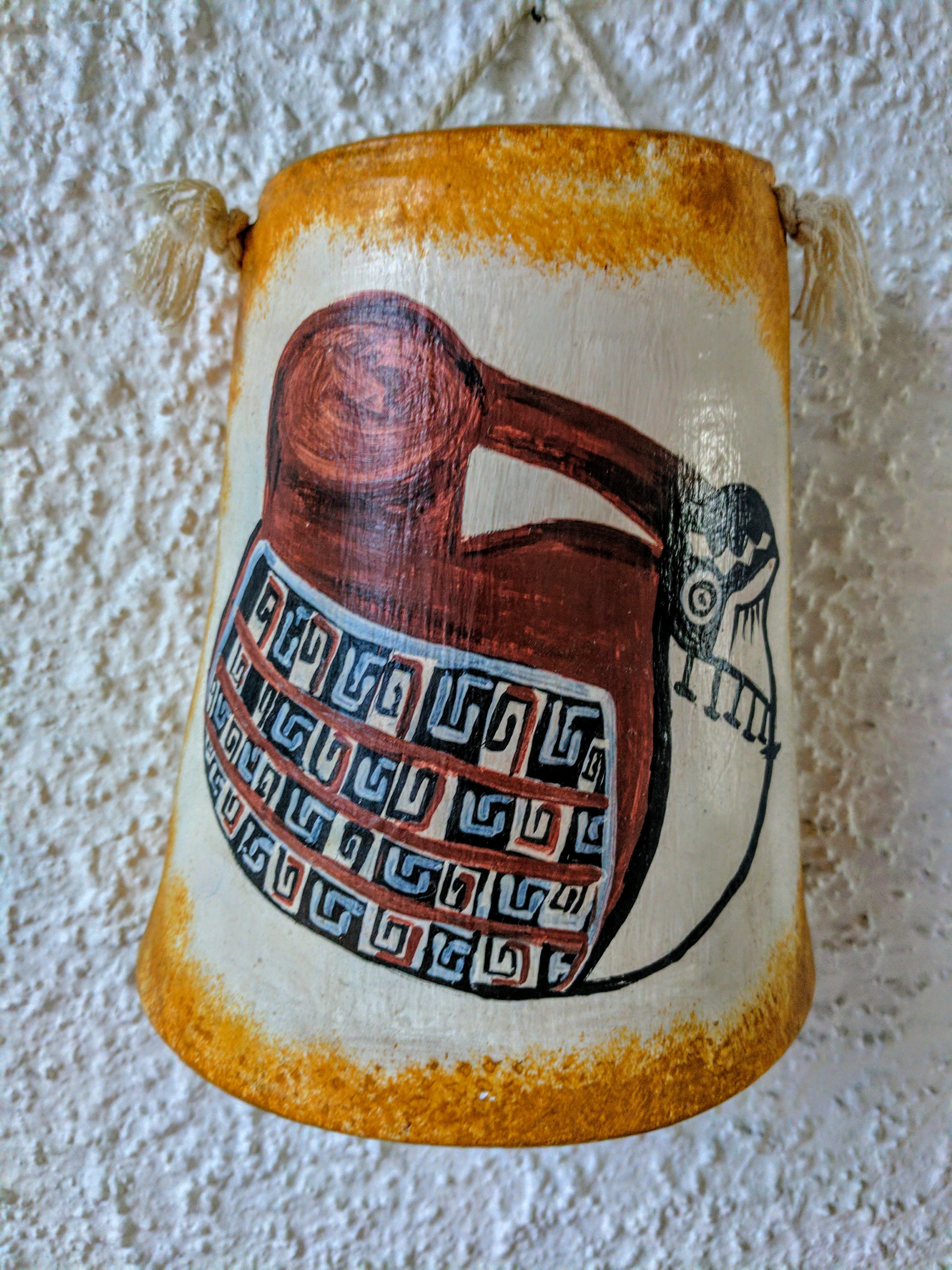

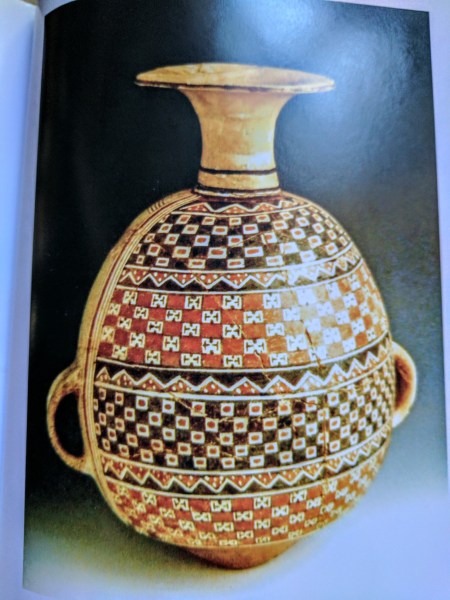

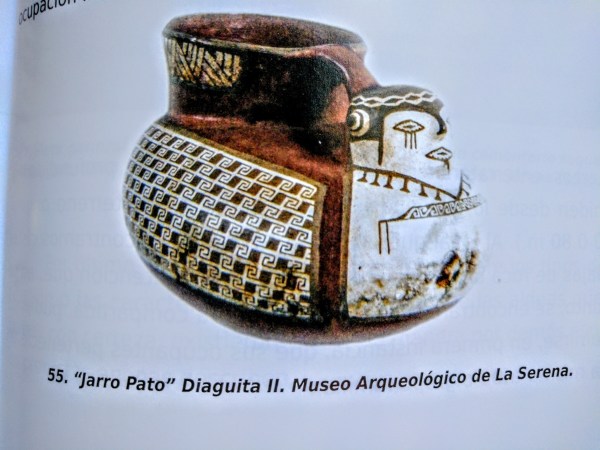

In artistic terms, the Diaguita are known above all for their

distinctive ceramics, which feature two-colored geometric

designs applied on a base of a third color. This kind of decoration

is found on a variety of vessels they produced, such as pots,

urns, duck-shaped pitchers, and bowls. The Diaguita’s

highly complex designs are thought to be representations

of shamanic visions; many of their vessels bear feline

motifs or people with feline features. Apart from

ceramics, the Diaguita also produced some of the geometric

designs and mask forms found in the rock art of the region.

Checking out Murchie

On the day we left La Serena, Kunza came to say Good-bye. Kunza or Cunza is an extinct Language Isolate once spoken in theAtacama Desert of Northern Chile. Likely he is a very old soul….

I have included two articles I found on the web talking about the Diaguita and their land claims and their relationship with Barrick Gold.

Nancy Yáñez is a professor in the Law Department at the University of Chile and codirector of the Observatory of Indigenous Peoples Rights.

Sarah Rea is an anthropology student at Harvard University. She conducted independent fieldwork in Chile in 2006, focusing on indigenous politics in the Huasco Valley.

DIAGUITA

Publication Date

December 2006

Author

Nancy Yáñez and Sarah Rea

Indigenous people in Chile’s Huasco Valley have held onto their land and their identity for 4,000 years despite conquerors, dictators, and a dominant culture that didn’t recognize their existence. Now they face a new threat, one that glitters.

Legend has it that it was the Inca leaders of Cuzco who told the Spanish colonizers that there were hidden riches in the south. Dreaming of gold, the Spanish, who had already taken the land and treasures of the native Peruvians, headed south for Chile to expand their colonial empire. Neither the Spaniards nor the leaders of the Incan empire could have imagined the magnitude of Chile’s natural resource fortune—now measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars—or the degree to which getting those riches would disrupt indigenous cultures.

This dynamic is still being played out today in the Huasco Valley of northern Chile, which is the traditional home of the Diaguita people. The 700-mile-long Huasco River is fed by glaciers and nourishes the lush vineyards, tropical fruits, avocados, and legumes of the Huasco Valley microclimate. The valley is known for its freshwater shrimp, artisan olive oil, grapes, Pisco (the national liquor), and Pajarete liqueurs. Unfortunately for the Diaguita, the Huasco Valley is also known for its gold, silver, and copper deposits.

The river is fed by two tributaries in the valleys of El Carmen and El Tránsito, the second of which is home to the Diaguita. Some locals believe the indigenous peoples imposed taxes on dried fruits to keep the Spanish out of El Tránsito, and others say the Spanish took the “better” valley and left the lesser for the native Diaguita. Today, the families of El Tránsito still have Diaguita indigenous last names such as Campillay and Huanchicay, and those in El Carmen have last names of Spanish descent like Rojas and Marín.

Chilean history students have always learned that the Diaguita pueblo, or community, existed only from a.d. 900 to 1500, and the Diaguita name was not spoken in public discourse between the Spaniards’ arrival and 2001, when a fieldwork study was carried out by the Chilean Commission for True History and New Treatment. In the course of that fieldwork, Diaguita descendants told stories of their recent ancestors, and archeologists began to share their artifacts with the local people. In 2002, the residents of the Huasco Valley established the Diaguita Cultural Center. Suspicious outsiders say that the Diaguita identity is being revived just to get indigenous benefits under Chilean law. The Diaguita, however, say that the Diaguita ethnicity has persisted for centuries. Community member Oscar Cubillos Cuello says, “The disappearance of the Diaguita name is the fault of the anthropologists who never came to our land to interview us. The ethnicity has always lived; it is not dead.”

On September 8, 2006, the government came to the same conclusion and passed Chilean Law 20.117, which recognized the “existence and cultural attributes of the Diaguita ethnicity and the indigenous nature of the Diaguita people.” That declaration has significant cultural implications, of course, but it also has major political ramifications. The recognition of the Diaguita as indigenous people gives them rights to their traditional lands, but a significant portion of those lands have already been appropriated by the state, and that land is now extremely valuable.

The Diaguitas’ land was taken from them not by the Spaniards during 16th century colonization, but in 1997, when the government claimed 40 percent of the Diaguitas’ territory and divided it into three haciendas. One of those haciendas, Chollay, is currently being developed by the Barrick Gold Corporation of Canada. In October 2006, Nevada, Ltd., a subsidiary of Barrick Gold, began the construction of Pascua Lama gold mine in the mountains above Huasco Valley. The company is digging a gorge about a mile long and 1,800 feet deep, where ore will be extracted and processed using cyanide (the standard method for processing gold ore). The corporation had proposed drilling into three glaciers, one of which feeds the Huasco River, until valley residents and international environmentalists protested in Huasco’s main city of Vallenar and in Santiago throughout 2005.

Swayed to some degree by the protests, the Chilean government barred the mining company from touching the glaciers, and with that most serious concern addressed, gave the project final approval in early 2006. The company itself claims it will minimize the social and environmental impacts of its operations. They will give the local government $60 million for agriculture and will invest a further $10 million in the valley’s towns. In addition, the mine has hired the most advanced mining experts and is using state-of-the-art technology. “It still puzzles me why there is so much controversy,” Pascua-Lama project manager Ron Kettles told the New York Times. “This is far and away the safest and most environmentally sensitive project that I’ve ever built in 40 years in this business.”

Certainly there are those among the 70,000 residents of the Huasco Valley who welcome the mine and hope to be selected as one of 5,500 workers employed there. Most residents of Vallenar, Huasco Valley’s humble palm-lined metropolis, speak fondly of the mining industry. The city was once the prosperous hub of the mineral region, but it has fallen on hard times and now has an unemployment rate of 18 percent. Many there see the Barrick mine as a source of potential economic revitalization for the city.

But for the 262 Diaguita families of the Agricultural Community of Huasco Alto, land is the crux of their identity and the mine is a threat. Local Diaguita say that the mine is “new colonization, by transnational corporations.” When asked what “being Diaguita” means to them, residents of the valley have a standard response: “I was born here.” Most inhabitants of El Tránsito Valley—and El Carmen, too, for that matter—have never left the valleys. Many tell stories of their parents meeting down-valley and moving to the interior to farm their grandparents’ land. Many of the Diaguita families who no longer own ancestral land have a combination of indigenous and Spanish blood, but they choose to identify as indigenous because they, too, value the land in Huasco Valley as their native ancestors did. Some Diaguita families traveled north to take advantage of employment opportunities in the gold and copper mining industries from the 19th to early 20th centuries, but most returned to Huasco. “It’s like a magnet,” say residents across Huasco Valley, from Huasco to Vallenar and into the interior. “You might leave, but you always find yourself coming back.”

The history of the Diaguitas’ land claims is as long and winding as the dirt road that traces the Huasco River up the valley—a road along which pedestrians, horseback riders, and local buses ride from Vallenar to the pueblos of the valley interior. The interior is called Huasco Alto, and various pueblos or communities have lived here since 4000 b.c. The Molle were followed by the Ánimas, Copiapó, and the Diaguita cultures. The Diaguita developed between a.d. 1000 and 1470, when they were invaded by the Inca, and 1540, when the Spanish arrived. The Spanish divided the land into a grid of large landholdings, on which they built haciendas and estancias. The natives ranched, farmed, and mined land belonging to the Spanish patrons, and paid a portion of their produce to them. Under this system, the indigenous people were assigned land and permitted to use it freely.

In the Huasco Valley, the indigenous community was divided by geographic location: Huasco Alto, Paisanaza, and Huasco Bajo. The majority of the native land that was not usurped by the Spaniards was found in the valley’s interior, Huasco Alto. The year 1750 is of great significance to the huascoaltinos, as the indigenous people mounted armed resistance against the state, which hoped to reduce their territory to the space between two mountain ranges in the valley of El Carmen. The indigenous people won the battle, and, in 1757, El Tránsito river valley became huascoaltino territory, creating an environment for the Diaguita people to live autonomously.

At the onset of the country’s independence, the Republic of Chile asserted a new form of control over Diaguita territory. Laws passed in 1823 and 1830 aimed to eliminate Chile’s indigenous communities altogether, transferring most of their property to the state through a process called reduction. The republic hoped for a Chile without natives, at least from Copiapó at the foot of the Atacama Desert to the lakes district. This area comprises the whole of the country’s inhabitable, temperate central valley suitable for lucrative agriculture, ranching, and mining. Fortunately, the authorities focused their efforts on the valleys surrounding Santiago. The huascoaltino Diaguitas were able to conserve most of the territory they have called home since before the Spaniards’ arrival.

In 1993, the Chilean government issued Law 19.253, politically legitimizing the right to organize around a social tradition or culture. This should have cemented the Diaguitas’ land claims, but under the law the Diaguita ethnicity was not recognized. Politicians and anthropologists and Huasco Valley residents alike had no idea that the Diaguita had survived colonization intact. Archeologists had not collaborated enough with locals to realize that many of their beliefs and customs were in line with those represented in the ancient ceramics, roofs, and graves they uncovered. Social anthropologists had not begun to rescue the family histories, pastimes, foods, and legends of living valley residents. As a result, local indigenous histories and regional colonial struggles have not been incorporated into elementary school history classes in Huasco Province. School children learn brief biographies of the prominent conquerors of central Chile but not about the battles their respective ancestors fought.

On August 22, 2006, the Huascoaltino Agricultural Community wrote a letter to President Michelle Bachelet about this situation, asking for official recognition of their overlooked identity. “At the beginning of the 1990s,” they wrote, “our Diaguita identity still had not been presented publicly, because we were accustomed to organizing ourselves like farmers and ranchers. Moreover, we had forgotten our own history, and our schools did not teach us, nor did they teach our children, about where we had come from and who we were . . . [but] up to this moment, we maintained our own property, and with it our customs and way of life remained intact.”

That letter, one of many sent by the agricultural community and the Diaguita Community Center since 2002, worked, and one month later the government recognized them. But that recognition may have come too late. The government gave final approval to the gold mine earlier this year, and all decisions concerning the land are now made by the mining corporation, which will certainly proceed with planned extractions. How will the Chilean government begin to repay the newly “re-identified” indigenous descendants who they have agreed to protect by law? The Diaguita will not forget that they were denied the right to partake in negotiations for the use of their land. For indigenous families, monetary compensation could never come close to recovering the loss of their land, their sustainable way of life, and the worldview those represent.

Nancy Yáñez is a professor in the Law Department at the University of Chile and codirector of the Observatory of Indigenous Peoples Rights.

Sarah Rea is an anthropology student at Harvard University. She conducted independent fieldwork in Chile in 2006, focusing on indigenous politics in the Huasco Valley.

Period

The Diaguita of Chile: Supporting the determination of an Indigenous people

March 30, 2009

For more than a thousand years, the Diaguita have made Chile their home and thrived as a culture within its borders. Today, they are recognized as a distinct indigenous community living in Chile’s Huasco Valley. They have formed a close relationship with Barrick Gold based on a shared mining history and a common focus for the future.

Barrick Gold’s Pascua-Lama project is located 45 kilometers away from the nearest Diaguita settlement, making them the company’s closest neighbors.

The history of the Diaguita begins around 1000 A.D., when the indigenous group first descended from the Andes mountain range to settle in Chile’s valleys. Anthropologist Franko Urqueta, who was hired by Barrick Gold to study the Diaguita and has since written a book on the culture, says the population flourished between the eighth and 15th centuries, settling in the Norte Chico valleys and growing to a population of nearly 30,000 at their peak.

The Diaguita formed an agrarian-based society, creating an extensive and highly efficient irrigation system able to sustain a large population. The ywere known as walking farmers – moving from the coast to the mountains depending on which climate would give them the best agricultural results. According to Urqueta, the Diaguita were an advanced society that valued art and artisans. Throughout Chile, they were known for their varied and beautiful pottery and weaving. These artisanal traditions continued despite years of submission, first by the Inca empire and then by the Spaniards. Today, less than 1,500 Diaguita remain, making their home in the Atacama Region, specifically in the Huasco Valley. One of the smallest of nine indigenous groups in the country, they are a tight-knit and vibrant community.

“Right from the beginning, we have respected the Diaguita and their ties to the land,” says Igor Gonzalez, president of Barrick Gold South America. “We opened up the channels of communication and invited members of the community to discuss issues, to openly ask questions and to work together with us on the Pascua-Lama project.” Globally, Barrick Gold actively engages with indigenous peoples in the areas where the company operates. The aim is to develop long-term relationships that are constructive and mutually beneficial.

Justa Ana Huanchicay Rodriguez (pictured) is a respected Diaguita Elder and president of the Diaguita Cultural Centre in Huasco Alto. She says the company’s support is helping the Diaguita address their greatest obstacles. “Our main challenge is to preserve our customs, traditions, family names and lifestyle for future generations,” Huanchicay said. “To me, that is our major challenge and Barrick Gold is helping to make that happen.”

Huanchicay came to live with her Diaguita grandfather in the Huasco Valley at the age of 12. She has fond memories of her grandfather working the field, sowing wheat, corn, beans and potatoes. “My grandfather Pedro was not an educated person, but he was very wise,” she said. “He told me the history of our people, the importance of agriculture to our livelihood and how it had to be maintained. Our roots are tied to the soil. Helping us thrive as an agricultural society by providing assistance to farmers is a very important aspect of Barrick Gold’s support for the Diaguita.”

In 2006, Barrick Gold set up the Agro-Forestry Assistance Program in the Huasco Valley. The program recognizes the importance of farming to the Diaguita and the challenges of working the land, particularly during the dry season that hits the region hard each year.

Under the program, farmers receive specialized training in animal health, crops and cattle vaccines. To date 107 Diaguita farmers have taken advantage of the assistance program. Cattle vaccines have been provided to 67 farmers and another 40 have received seeds and technical support to help improve crop yields.

Diaguita artisanal traditions have been passed down through generations. Barrick Gold engaged Diaguita artisans, primarily women, to hold workshops and teach skills such as pottery and weaving to a new generation of Diaguita. More than 120 people have already become certifi ed in a variety of artisanal traditions through these workshops, which involve 60 hours of study. In addition to learning the ancient artistry, participants received commercial training to enable them to sell their work nationally and internationally and earn an income.

Already, Barrick Gold has sponsored these artists to attend several cultural and commercial exhibitions, most recently in Santa Cruz, Chile.

Paula Alcayaga is a 24-year old artisan who uses the art of the yard loom to weave beautiful work. She is a graduate of Barrick Gold’s looming workshop and was recently sponsored to attend the Santa Cruz exhibition. She came away amazed at the difference it made to her income and pleased with the contacts she made for future sales. “The company has assisted us with the recovery of Diaguita artisanal work,” Huanchicay said. “With Barrick’s support, we are able to hold courses in various techniques and later exhibit them successfully. We hope this support will continue.”

After years of struggling for official recognition, the Diaguita were granted legal status as a distinct ethnic group by the Chilean government in 2006. Following passage of legislation by the Chilean Congress in July 2006, President Michelle Bachelet signed into law recognition of the Diaguita people in August, 2006.

Subsequently, Barrick Gold agreed to provide free legal assistance to individuals seeking to gain official status as Diaguita and be eligible for government benefits. More than 20 people sought out this legal support and were later recognized by the government. Today in Chile, approximately 600 people have official status as Diaguita.

Five years earlier, the company also set an important precedent. When submitting its Environmental Impact Assessment for the Pascua-Lama project to authorities in 2001, Barrick Gold explicitly identified the Diaguita as a distinct ethnic group residing close to the project. This marked the first time this designation had been associated with the indigenous group. This key document was reviewed extensively by government and the public and laid the foundation for the company’s future relations with the Diaguita in the Huasco Valley.

Huanchicay says Barrick Gold’s acknowledgement in this way was a stepping stone to gaining official recognition. “Many people helped us to attain this,” she said. “From local authorities to members of the House of Representatives, many people were involved. This includes the considerable efforts of the Diaguita cultural centre in Copiapó and our centre here in Alto del Carmen. Together we all pushed towards the same goal.”

To increase awareness of Diaguita culture, Barrick Gold sponsored the writing of Etnia Diaguita, Urqueta’s book about the known history of the Diaguita. The book is now being used in schools in the Atacama Region and elsewhere to teach the next generation about this distinctive indigenous culture. A documentary film was also sponsored by Barrick Gold to give the Diaguita an opportunity to showcase their culture. The film features first-person accounts from Diaguita from all walks of life, recounting ancestor stories and describing their customs, language and traditional activities. More subtly, the film reveals the determination of a people bound by a shared identity who, with little outside support, have managed to endure. The documentary was screened by members of the community on the second anniversary of the group’s official recognition by the Chilean government at an event in Copiapó in 2008.

“To us, the film is a tribute to our effort and our people,” Huanchicay said. “It is a way for our children to get to know the Elders, speaking in their own words.”

At the packed film screening, members of the Barrick Gold team who had championed the Diaguita cause in the region received a special blessing and thanks from one of the community’s spiritual leaders.

“Barrick’s future in the Huasco Valley and the future of the Diaguita are interconnected,” says Gonzales. “We will continue to ensure this community and the region benefit from Pascua-Lama.”

Franko Urqueta is an anthropologist specializing in the study of ethnic groups in Chile. He studied anthropology at the University of Chile in Santiago and has worked with several ethnic groups, namely the Mapuches, Atacamenos and Coyas. In 2005, Urqueta was sponsored by Barrick Gold to study the Diaguita culture. He discusses his research with Beyond Borders’ editor Nancy White.

Who are the Diaguita? Where do they make their home?

The Diaguita were officially recognized as a distinct indigenous community by the Chilean government in 2006. Approximately 600 people have official status as Diaguita. They live in the Huasco Valley, which is part of their original pre-Colombian territory. In all the other valleys in the northern area, as well as in the rest of Chile, the Diaguita population has disappeared. Some individuals bearing Diaguita names continue to live in the Huasco Valley, but they do not constitute an indigenous group. The remaining Diaguita exist only in the upper Huasco Valley.

Why was the book “Etnia Diaguita” created?

The book was an opportunity to compile the limited pre-existing data on the Diaguita and support further study. It examines past and current culture and some of the challenges this community faces.

What makes the Diaguita culture so unique and so resilient?

A key characteristic of Diaguita people is their capacity to adapt. Throughout their history, the Diaguita came into contact with other groups, such as Incas, Spaniards and then the Republic of Chile, that tried to impose their customs and traditions. By adapting to new authorities, the Diaguita were able to maintain their identity and endure as a people for more than a thousand years.

Some critics claim that the culture of the Diaguita will be threatened by mining above the Huasco Valley? Do you agree?

Most of the people who criticize mining activity in the valley do not live in the valley. They also have very limited knowledge of Diaguita culture. From the beginning, the Diaguita have mined gold. Five hundred years ago, they developed mining activities in this valley – becoming the first miners in this inpart of Chile. They paid taxes to the Peruvian Inca Empire in gold and were also gifted goldsmiths. The Diaguita population have combined their traditional agricultural and cattle raising activities with small-scale mining. Barrick Gold has introduced itself as a respectful neighbor, aware of this mountain culture and committed to safeguarding its identity.

Tags: Diaguita, Kunza, Las Serena, Terra Diaguita Boutique Hostel

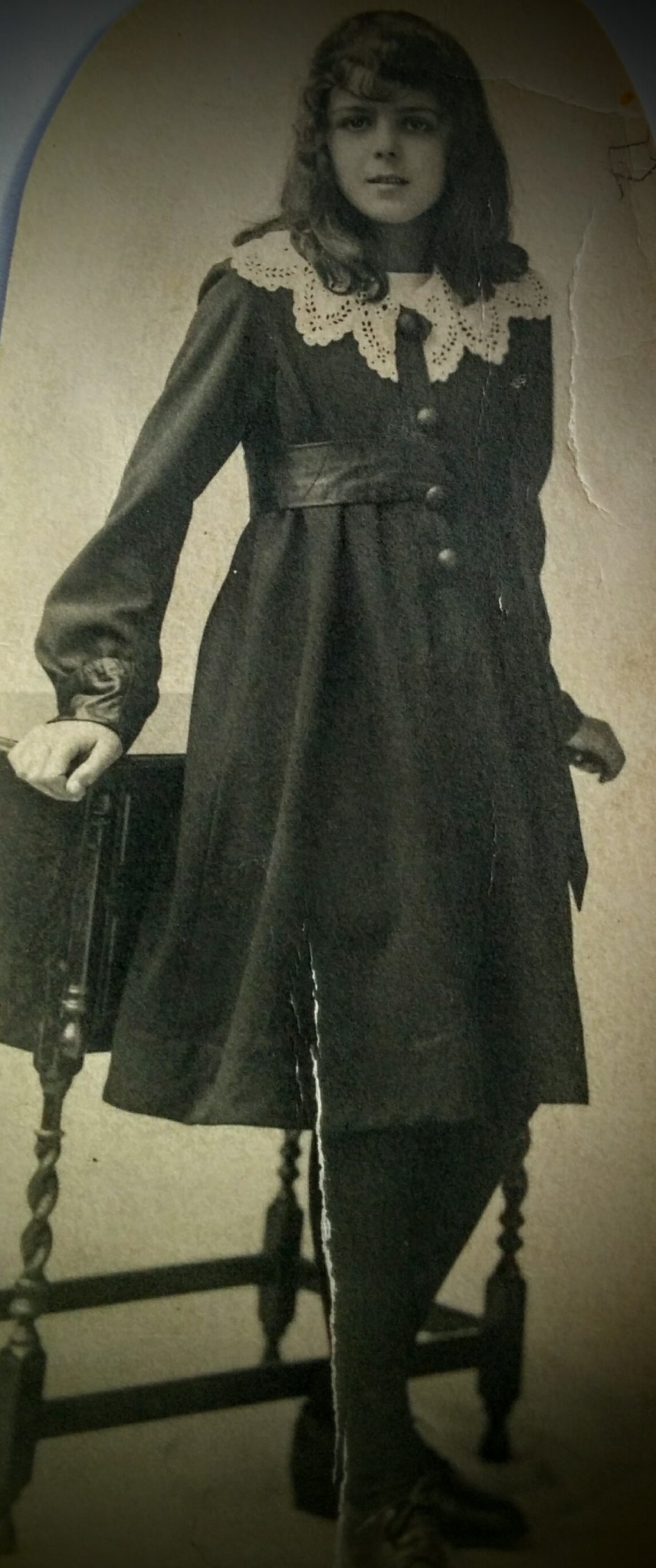

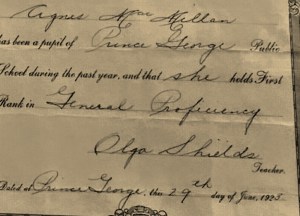

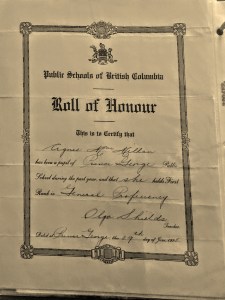

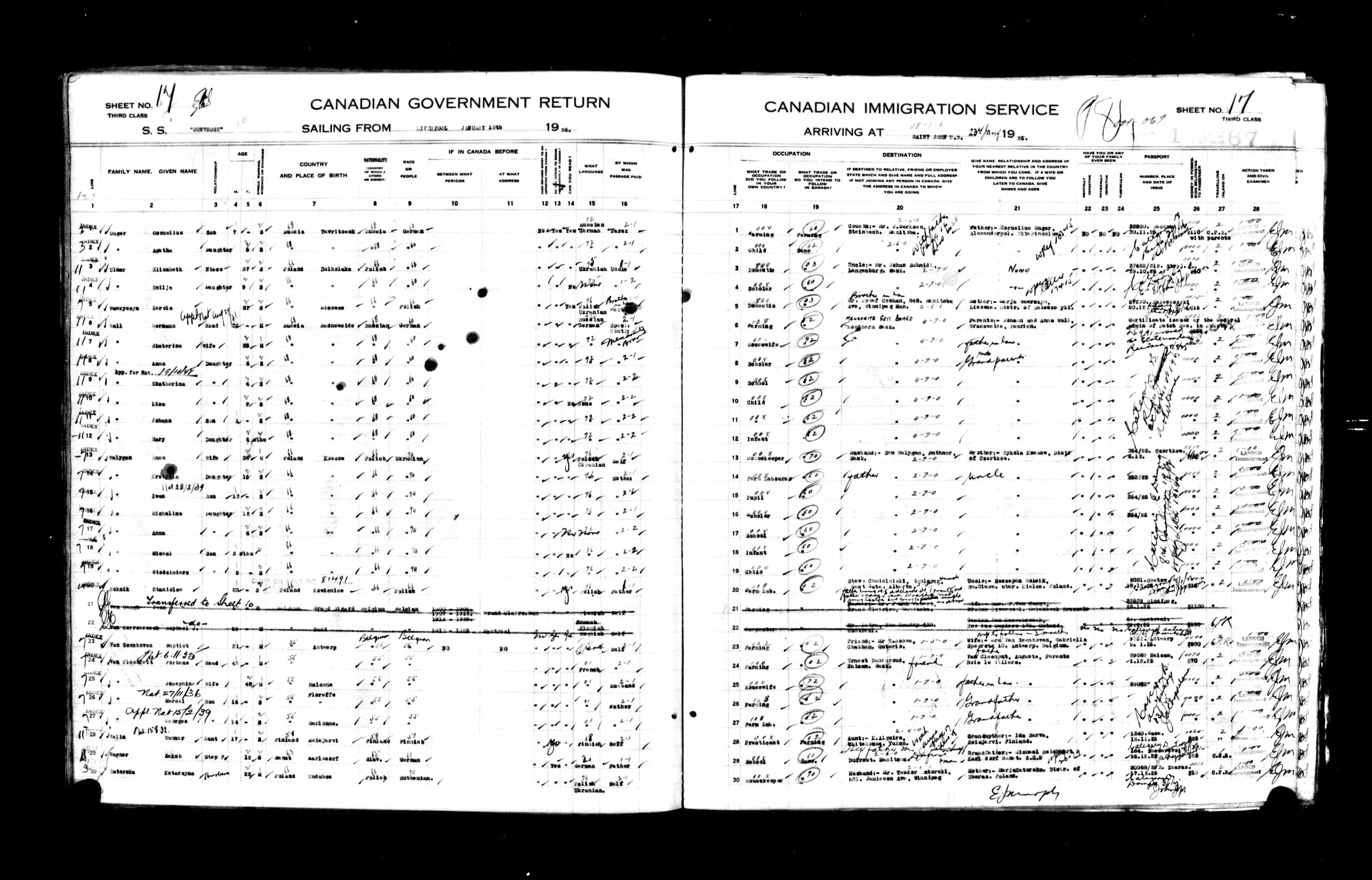

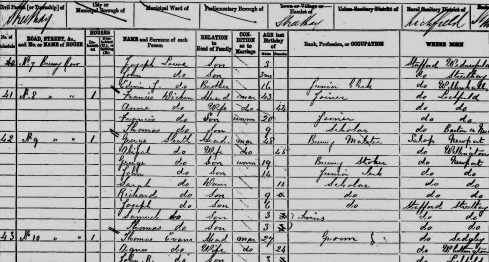

Hermann 36, Katherina 35, Anna 6, Katherina 4, Lisa 2, Johann 1+ and Mary 6 mo. Departed Liverpool England for St. John New Brunswick arriving 25Jan1926 ancestry.co.uk

Hermann 36, Katherina 35, Anna 6, Katherina 4, Lisa 2, Johann 1+ and Mary 6 mo. Departed Liverpool England for St. John New Brunswick arriving 25Jan1926 ancestry.co.uk

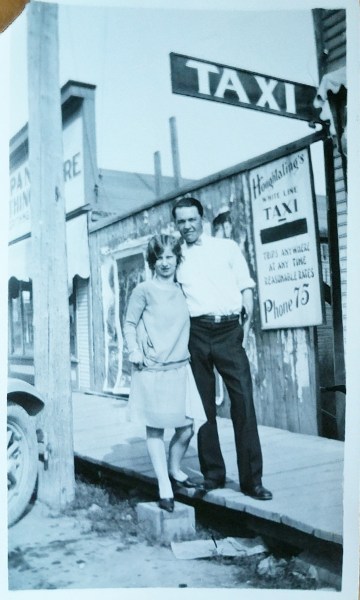

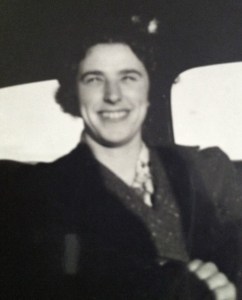

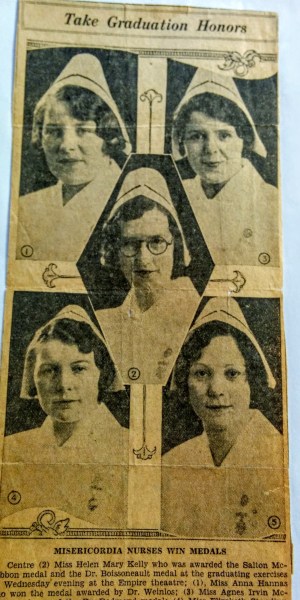

Mom entered the Misericordia School of Nursing in 1928. She would have been 19 years old. The hospital at that time was operated by the Sisters of the Misericorde out of Montreal. The Sisters of Misericorde were a Religious Congregation founded by Marie Rosalie Cadron Jettre (1794 – 1864) in Montreal Quebec in 1848 and was dedicated to nursing the poor and unwed mothers. The congregation spread into Western Canada, establishing the Misericordia Hospital in 1900. The Sisters of Misericorde operated the hospital until the 1970s, when it became part of what is now Covenant Health, a Catholic health care provider operating 18 facilities across Alberta, in cooperation with AHS

Mom entered the Misericordia School of Nursing in 1928. She would have been 19 years old. The hospital at that time was operated by the Sisters of the Misericorde out of Montreal. The Sisters of Misericorde were a Religious Congregation founded by Marie Rosalie Cadron Jettre (1794 – 1864) in Montreal Quebec in 1848 and was dedicated to nursing the poor and unwed mothers. The congregation spread into Western Canada, establishing the Misericordia Hospital in 1900. The Sisters of Misericorde operated the hospital until the 1970s, when it became part of what is now Covenant Health, a Catholic health care provider operating 18 facilities across Alberta, in cooperation with AHS

Individual Rooms

Individual Rooms

Pyramid Power were of interest to many people. My Dad was a voracious reader and in his retirement, visiting the Public Library was one of his main passions. He would bring home the most interesting books which we would often discuss during those long dark winter evenings.

Pyramid Power were of interest to many people. My Dad was a voracious reader and in his retirement, visiting the Public Library was one of his main passions. He would bring home the most interesting books which we would often discuss during those long dark winter evenings.